Children’s video games are oversimplified

January 23, 2023

Today’s young adults that grew up on video games will probably have fond memories of the fun gameplay, interesting characters and goal-driven stories most games from the late 1990s and 2010s had.

Games targeted towards younger audiences – about 6 to 12 years old – had a good balance of gameplay that was easy to understand, but challenging. The stories were simple, but thought-provoking, and the themes and dialogue were advanced, but not inappropriate.

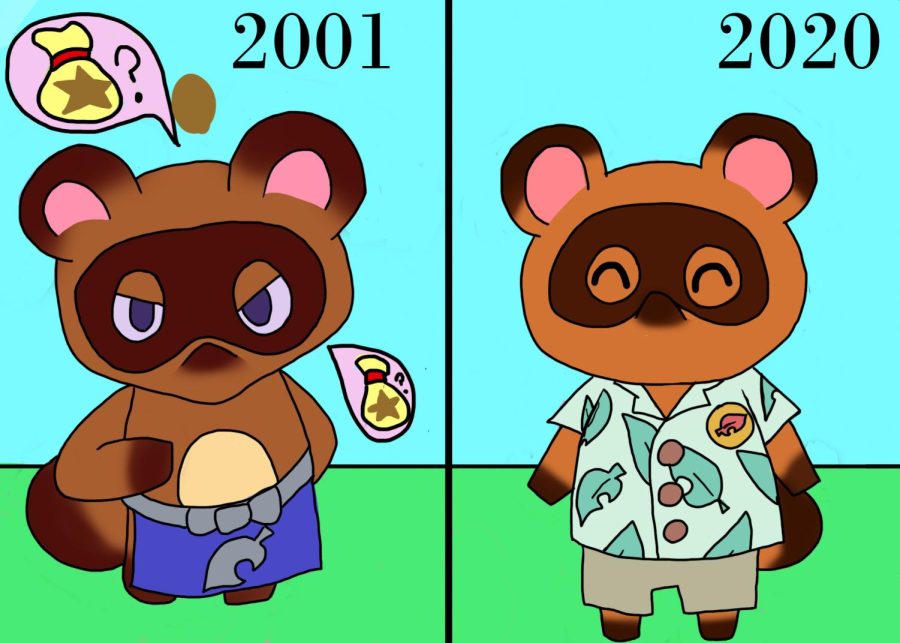

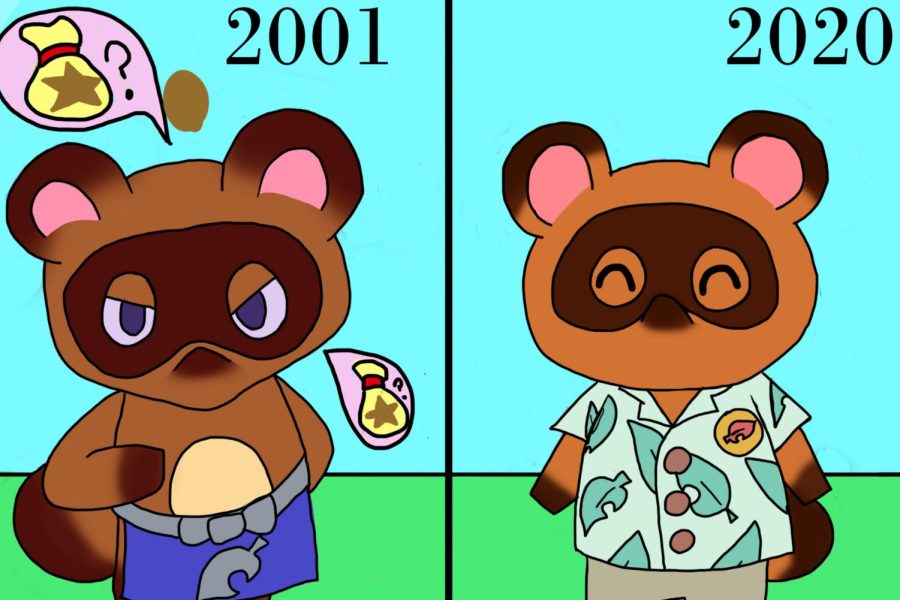

I don’t see these elements in children’s video games, and even some children’s media, as much these days. I’m channeling the “back-in-my-day” energy by saying that I’ve noticed modern children’s video games are too childish, even for the game’s targeted age range. It’s concerning when a 12-year-old says that “Pokémon Sword” and “Pokémon Shield” are too easy.

English Professor Victoria Banks has a master’s in professional video game writing with a focus on interactive narrative design and script writing. She has had personal experience with the issue in her previous career field.

“With children’s games in particular, that is a huge problem I noticed, and it’s in all kids’ writing and even television shows,” Banks said. “A lot of children’s media will dumb down the content and it’s kind of belittling, in a way.”

One rule that I learned in creative writing is to trust the audience to piece together things on their own and not spoon-feed them the story. Not doing so is the creator telling the audience that they are not smart enough to interpret the story.

“I think there is… that lack of trust in the audience to be able to navigate [the] story and interpret ideas and be able to think critically,” Banks said.

Some people will often dismiss poor story writing by saying “it’s just a kid’s show/video game/book.” Banks uses “Avatar: The Last Airbender” as a shining example of children’s media and how great it can be. She said it explored themes of relationships, philosophy and morality without being inappropriate for children and still being humorous.

“That line of ‘It’s just a kids’ show, it’s just a kids’ game,’ is very dismissive of the quality of work that is being produced. So, it almost excuses bad writing, it excuses bad gameplay because it’s for kids,” Banks said. “No, it should still be entertaining. It should still be fun. And a kid is going to understand that too.”

Some children’s games will funnel the players to go to certain places instead of letting them explore and figure out where to go for themselves. Video games that have the option to remove on-screen tips and other similar mechanics feel like a godsend when it should be the standard.

“Pokémon Sword” and “Pokémon Shield” received backlash when the game developers announced that the experience share mechanic would be permanent. This took away the players’ option to make the game more challenging. Also annoying are companions such as Fi in “The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword” who tell players what to do instead of letting them figure it out.

Psychology Instructor Bridget Tweedy, who is a video game hobbyist, said that society does not give “any weight to the intellectual challenge and the motor skills and the hand-eye coordination” children receive from playing video games.

The National Institutes of Health conducted a study on 2,000 children that do and do not play video games to measure their cognitive development.

“…those who reported playing video games for three hours per day or more performed better on cognitive skills tests involving impulse control and working memory compared to children who had never played video games,” NIH reported in a news release.

Tweedy compares the hand-holding in some children’s games to how parenting styles have changed throughout each generation.

“The gen Xers and the millennial parents are doing more hand-holding and I’m not sure why. Because it is ultimately more harmful to cognitive development…” Tweedy said. Using her son as an example, she said she will point him in the right direction, but not do something for him so that he can figure it out and develop critical thinking skills.

Like parents with their children, game developers need to be able to trust their child audiences’ intellectual capabilities when it comes to understanding complex themes and carving out a path for themselves within the interactive environments they are creating. Children are smarter than adults give them credit for, and it’s time we started letting them show it.

Steve Ince • Jan 24, 2023 at 4:49 am

Excellent piece!