Air raid sirens, towering flames and panicked people in the streets—these are sights and sounds all too familiar to Studio Ghibli director Hayao Miyazaki, who opens the studio’s latest film, The Boy and The Heron.

Released in the West the previous year, the film won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature and brought the honor back to Japan.

This international recognition is nothing new to Studio Ghibli and its team of animators, producers, writers and its esteemed director.

The Boy and The Heron is Ghibli’s 14th film in a lineup of artistry that began in 1985. In spite of multiple claims of retirement, Studio Ghibli’s head, Miyazaki, has found it difficult to step away from filmmaking, being almost 80 at the start of production.

“I’m prepared to die before it’s finished,” Miyazaki said in the documentary Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki. “I’d rather die that way than die while doing nothing. To die with something to live for.”

This idea seems to be the core theme of Miyazaki’s latest feature film. The Boy and The Heron follows Mahito (which means ‘sincere one’ in Japanese), a young boy dealing with the recent death of his mother in an attack on their village during World War II.

His father remarries soon after, leading to a new life in a new place still struggling through the dangers and restrictions of the war. Mirroring moments of Miyazaki’s own life, The Boy and The Heron asks its viewers a question the director himself cannot seem to fully answer: How do you live?

Based on a book that carries this question as its title, the film gradually becomes more surreal and dreamlike, taking Mahito—and the audience—on a long journey filled with both horrifying and mystical imagery.

Like other films in Ghibli’s gallery, recurring themes of love, loss, grief and acceptance reveal themselves throughout the movie.

Beginning in the Japanese countryside and continuing into a dreamworld where nothing is as it seems, the setting plays as vital a role in the story as the characters, with rich, vibrant colors contrasted by the darkness of Mahito’s situation.

“My films show the world’s beauty, beauty otherwise unnoticed,” Miyazaki said. “That’s what I want to see.”

For nearly half a century, Studio Ghibli has produced a catalog of adventures featuring a colorful, beloved cast of characters that have resonated with generations of viewers around the world.

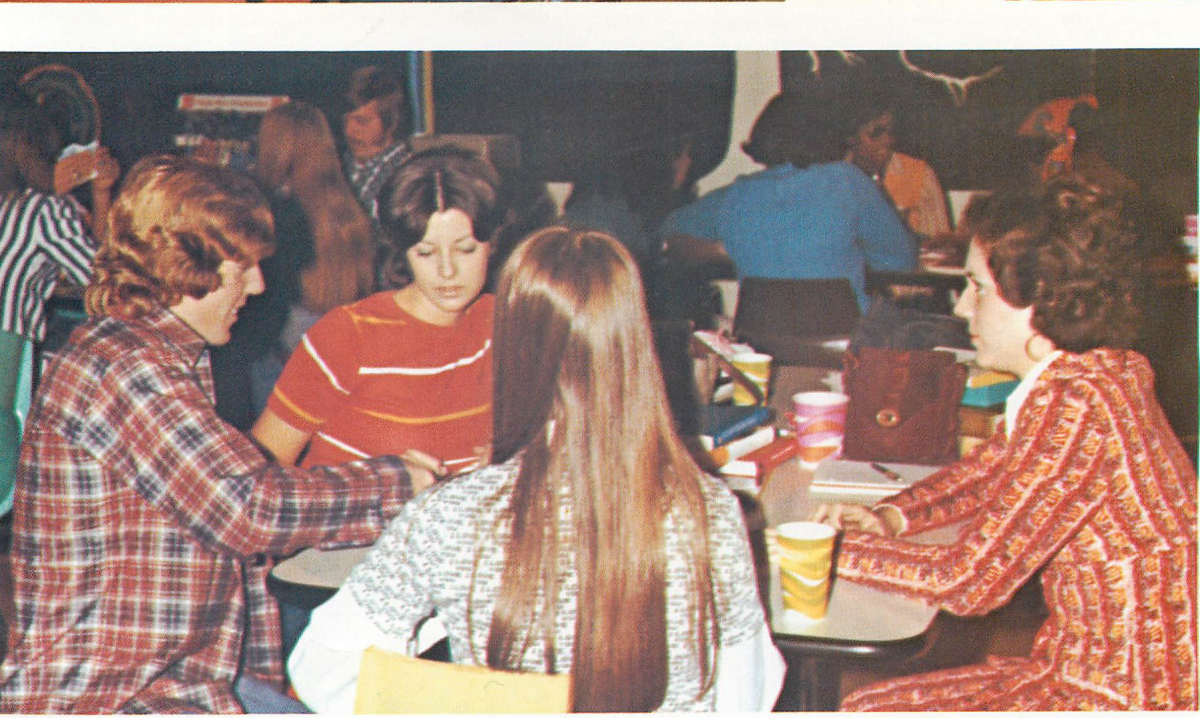

Many Studio Ghibli fans become lifelong admirers, watching the films as children and later developing a deeper appreciation for movies and art.

Film Production student Addams Kelley reflected on the 2008 movie Ponyo: ‘It was the very first one I watched as a kid, and it’s a big part of my childhood!’

Film student Joseph McDaniel shared his thoughts on Ghibli’s 1989 movie Kiki’s Delivery Service: ‘When you look at that film from the perspective of an artist, its themes of burnout from doing what you love hit hard.’

These sentiments are common among Studio Ghibli fans. While many Ghibli films feature nuanced characters on grand adventures, their messages resonate with many areas of life.

This reflects the studio’s celebrated history of conveying universal themes that both children and adults can enjoy.