In Netflix’s “Bridgerton,” Shonda Rhimes reinvents how to present race in a period piece

Netflix struck gold with their release of the Regency era romance Bridgerton. In this semi-fictionalized world, brought to us by Shonda Rhimes’ new major deal with Netflix, race does not stop a person from belonging to a particular class.

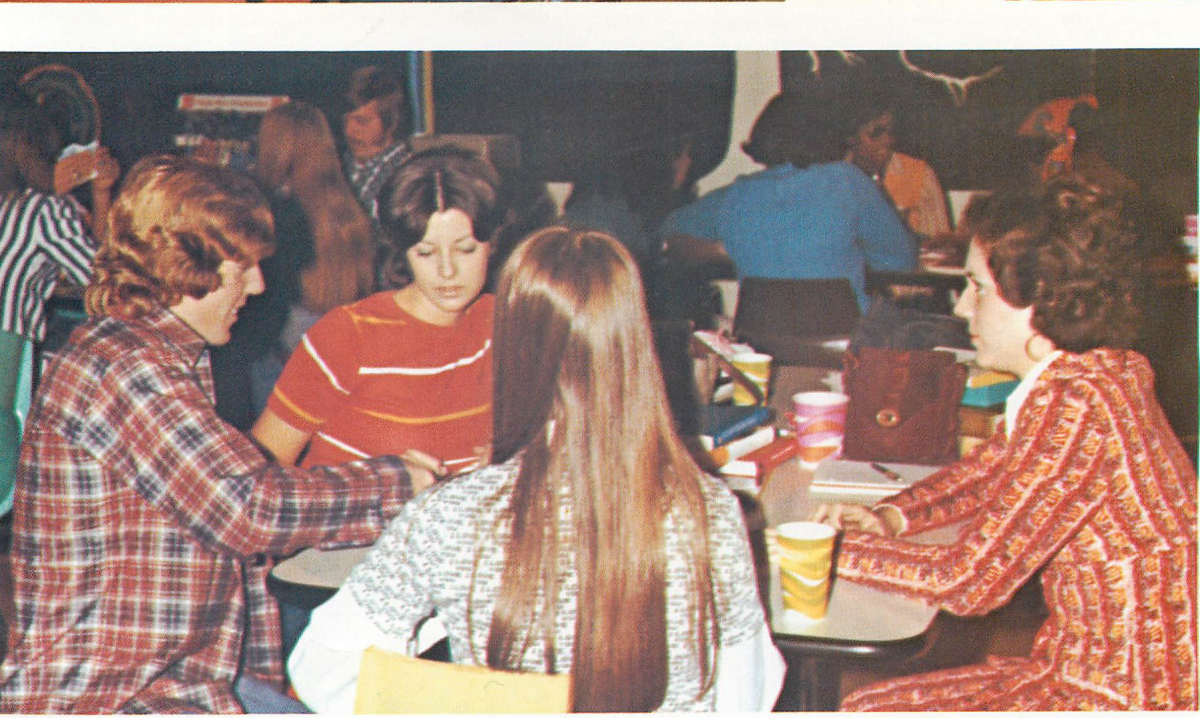

The show is a vibrant and indulgent dose of escapism. The series places luxurious ball gowns against the backdrop of lush garden parties as the young ladies and gentlemen of Regency era England try to find love.

The partygoers traditionally dance to classical interpretations of pop songs, like Ariana Grande’s “Thank U, Next” by the Vitamin String Quartet. Julie Andrews’ narration of the story only enhances the elegant production.

The hit show is based on the best-selling novel series by Julia Quinn, and it breaks barriers when it comes to race. This leads to the point of contention for those arguing the series is historically inaccurate.

In the first episode, we meet an African-American male lead, Regé-Jean Page, who plays the Duke of Hastings. He is the most eligible bachelor out of the group and all the women want to marry him. Yet still, he has sworn off marriage completely, that is until he meets Daphne Bridgerton, a sought-after white girl whose future becomes intertwined with his unexpectedly.

At first glimpse, Bridgerton is a color-blind fantasy liberated from the racial discourse. But as history goes, we know that’s not accurate.

By the third episode, racial issues are finally discussed in a seemingly frivolous way. While explaining the importance of love, Lady Danberry, one of the show’s Black matriarchs, reveals that their “white” king fell in love with a “Black woman,” Queen Charlotte.

Danberry continues and says the bond between the King and Queen is why their society is without discrimination. Danberry continues, “the king’s love for Queen Charlotte brought the country together. It allowed people of color to gain titles and be treated with dignity and respect.”

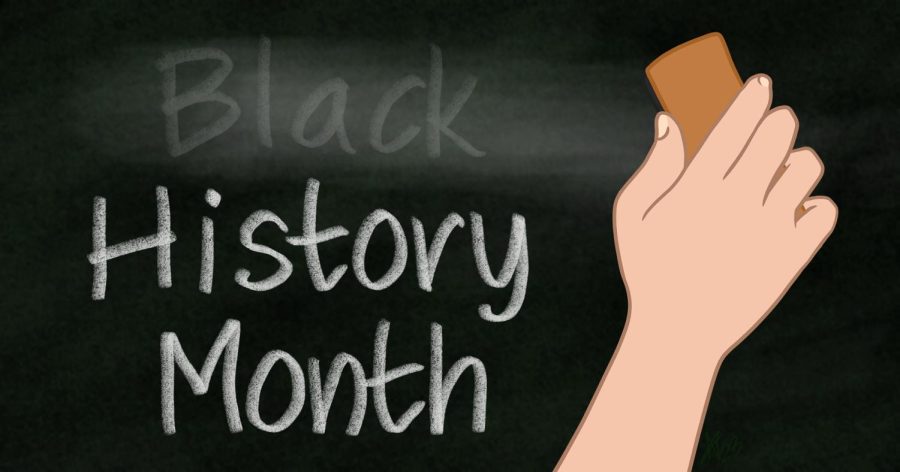

That’s the first and last time we hear anything about race or racism in the entire season. Even though race discussions are important, it was refreshing to see people of color not be weighed down by their oppressors. Here in Bridgerton they are seemingly no different than anybody else.

In an interview with Times, showrunner Van Dusen explains his reason for this version of Regency England. It came about when he learned that the actual Queen Charlotte might have been a Portuguese royal family member with African ancestry.

“It made me wonder what that could have looked like,” he said, “Could she have used her power to elevate other people of color in society? Could she have given them titles and lands and dukedoms?”

However, as Barack Obama’s presidency proved, a country being led by a Black person does not suddenly make racial issues settle.

Within Bridgerton, there needed to be more clarification of how race played into this society and what Queen Charlotte accomplished for people of color.

Despite the race-related flaws, Bridgerton does try to give us an accurate depiction of England’s demographics.

Other period dramas like “Downton Abbey” and “Pride & Prejudice” lead audiences to believe that only white people lived in those spaces at the time. The lack of diversity in period dramas only preserves this false narrative.

Black and brown people have had a presence in England for centuries and they weren’t just servants and slaves. Bridgerton shows this with Will Mondrich, a Black boxer based on famous real-life boxer Bill Richmond, who rose to success in 19th century England. The representation was needed and appreciated.

Hopefully, moving forward, other period pieces move in a more diverse direction as Bridgerton has. Then we can analyze them for their content, not by their lack of inclusivity.