Revisiting the racist history behind Thanksgiving: a whitewashed holiday we should denounce

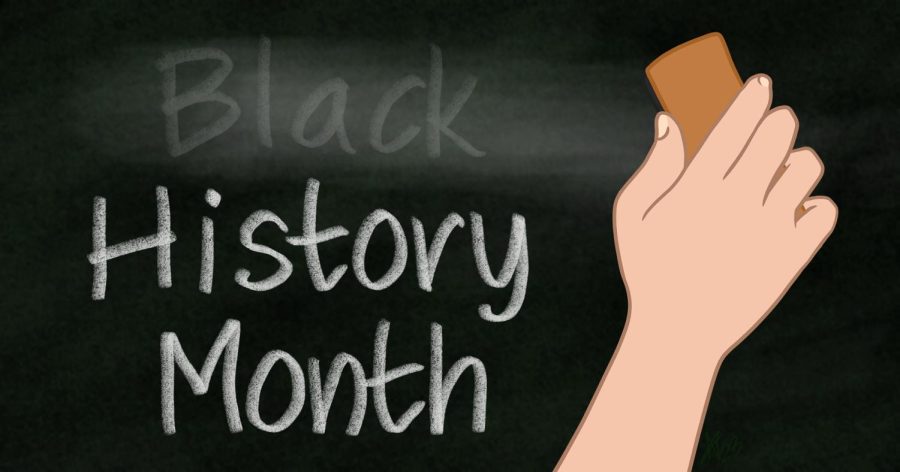

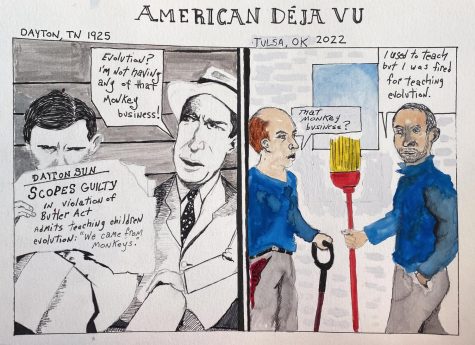

Like so much of American history, the traditional telling of Thanksgiving was created to mask a dark past.

Growing up, we learned the first Thanksgiving was a joyous feast between the Mayflower pilgrims and friendly, local Native Americans. As kids, we blindly celebrated the holiday with classroom feasts and paper turkeys, only to later learn that the story of cultural acceptance we were fed was a lie.

Thanksgiving has a long-disputed history. The most prevalent version tells of the 1621 feast where Plymouth pilgrims thanked the Wampanoag tribe for helping them survive in the New World. According to TIME, the celebration lasted three days with deer, fowl and corn on the menu.

However, the pilgrims probably wouldn’t have considered the 1621 Plymouth feast as the first Thanksgiving. The pilgrims actually felt a sober day of prayer in 1623 was the first Thanksgiving.

Others viewed 1637 as the true origin of Thanksgiving when Massachusetts colony governor, John Winthrop, declared a day of Thanksgiving to celebrate colonial soldiers. However, this story doesn’t sit quite the same, knowing that the same soldiers had previously slaughtered 700 Pequot men, women and children in what is now Mystic, Connecticut.

Of the three versions, the first is the one we hear the most and makes for the best celebration. But given a broader context, the story isn’t so blissful.

“According to “Historic Contact: Indian People and Colonists in Today’s Northeastern United States,” authorities in Plymouth began asserting control over “most aspects of Wampanoag life,” as settlers increasingly ate up more land,” writes Aine Cain for Business Insider.

Settlers increasingly took up more land and disease had already reduced the Native American population in New England by as much as 90 percent from 1616 to 1619. No matter how welcoming the pilgrims were, there’s no denying they caused the deaths of thousands of indigenous people.

Massasoit, the Wampanoag’s paramount chief called the sachem, proved to be an essential ally to the English settlers in the years following Plymouth’s establishment. He set up an exclusive trade pact with the newcomers and aligned with them against the

French and other local tribes like the Narragansetts and Massachusetts.

Just one generation later, that alliance was weakened beyond repair.

By the time Massasoit’s son Metacomet, known to the English as “King Philip,” inherited leadership, relations had dissolved. King Phillip’s War was sparked when several of Metacomet’s men were executed for the murder of John Sassamon.

Wampanoag warriors responded by embarking on a series of raids, and the New England Confederation of Colonies declared war in 1675. The neutral Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations were eventually dragged into the fighting, as were other tribes nearby.

The war was bloody and devastating.

Springfield, Massachusetts, went down in flames. The Wampanoag abducted colonists for ransom. English forces attacked the Narragansetts on a bitter, frozen swamp for harboring fleeing Wampanoag. Six hundred Narragansetts were killed, and the tribe’s winter stores were ruined. Colonists in far-flung settlements relocated to more fortified areas. Simultaneously, the Wampanoag and allied tribes were forced off their land and fled their villages.

The colonists ultimately aligned with several tribes like the Mohigans and Pequots, despite initial reluctance from the Plymouth leadership.

Meanwhile, Metacomet was dealt a harsh blow when he went to New York seeking allies. Instead, he was rejected and attacked by the Mohawks. Upon returning to his ancestral home at Mount Hope, he was shot and killed in a final battle.

The son of the man who had sustained and celebrated with the Plymouth Colony was then beheaded and dismembered. His remaining allies were either killed or sold into slavery in the West Indies. The colonists had “King Phillip’s” head on a spike and displayed it in Plymouth for 25 years.

The war’s ultimate death toll could have been as high as 30 percent of the English population and half of the Native Americans in New England.

This war was just one of the brutal but faintly remembered early colonial conflicts between Native Americans and colonists in New England, New York and Virginia.

The popular image of Thanksgiving is a diluted and altered version of the violent truth. By perpetuating a story of cultures coming together, we erase the struggles of indigenous people.

For some, modern-day Thanksgiving may be a celebration of people coming together. But to others, it is a painful rewrite of their history.

J. Kess • Oct 31, 2021 at 2:13 pm

I would prefer to think there WAS a great effort to extend friendship by the pilgrims…One can see, however that ‘war’ was a way of life with the Indians ‘outside’ of their particular tribe…just as in Africa…Middle East and anywhere humans are ‘tribal’…Indeed, white Europeans were not the first to ‘discover’ America…But, most likely, neither were the Indians… I believe the earth was, once, ONE continent, UNTIL GOD divided it by the oceans & seas because of the actions of man! And, I believe that the Indians were ‘not’ originally here, but came from the areas of the Orient and other cultures migrated upward from what we know as Central America, as they are currently doing again…Thus, white people were simply a long line of humans who made their way into what we, now, call the United States… However, it appears that ‘tribal groups’, such as your’s are seeking to, once again, conquer & DIVIDE!!!!! This ‘conquering’ has gone on since the beginning of time with evil greed of man…And, with that: “To the ‘Victor goes the ‘spoil’!…which , according to history is NOT returned or reparations or retribution’s paid!!!

Joan A Wells • Nov 26, 2020 at 3:23 pm

Hopefully, this holiday will go the way of Columbus Day.