Cicadas are in the forecast — what you should know about Brood X

Hide your power tools and plug your ears. After spending 17 years underground, cicadas are set to swarm in the summer.

Brood X, aka the Great Eastern Brood, is a large group of periodical cicadas or “magicicadas” that emerges every 17 years across 11 states, including Georgia. Brood X is composed of three different species: Magicicada septendecim, Magicicada Cassini, and Magicicada septendecula.

Jason Christian, instructor of biology at GHC, remembers the last emergence of Brood X in 2004. “I was always an avid outdoorsman, so the large density of them in nature is always a memorable experience if you should find yourself outside when they are out,” said Christian. Christian has studied ecology for over 10 years, and in his 8 years at GHC, he has helped many of his students collect and identify cicadas for insect projects.

The periodical cicadas of Brood X are not the same as the annual cicadas that set the ambiance of Georgia summer evenings each year. While annual cicadas have populations that emerge every year, periodical cicadas emerge in 13 or 17-year cycles.

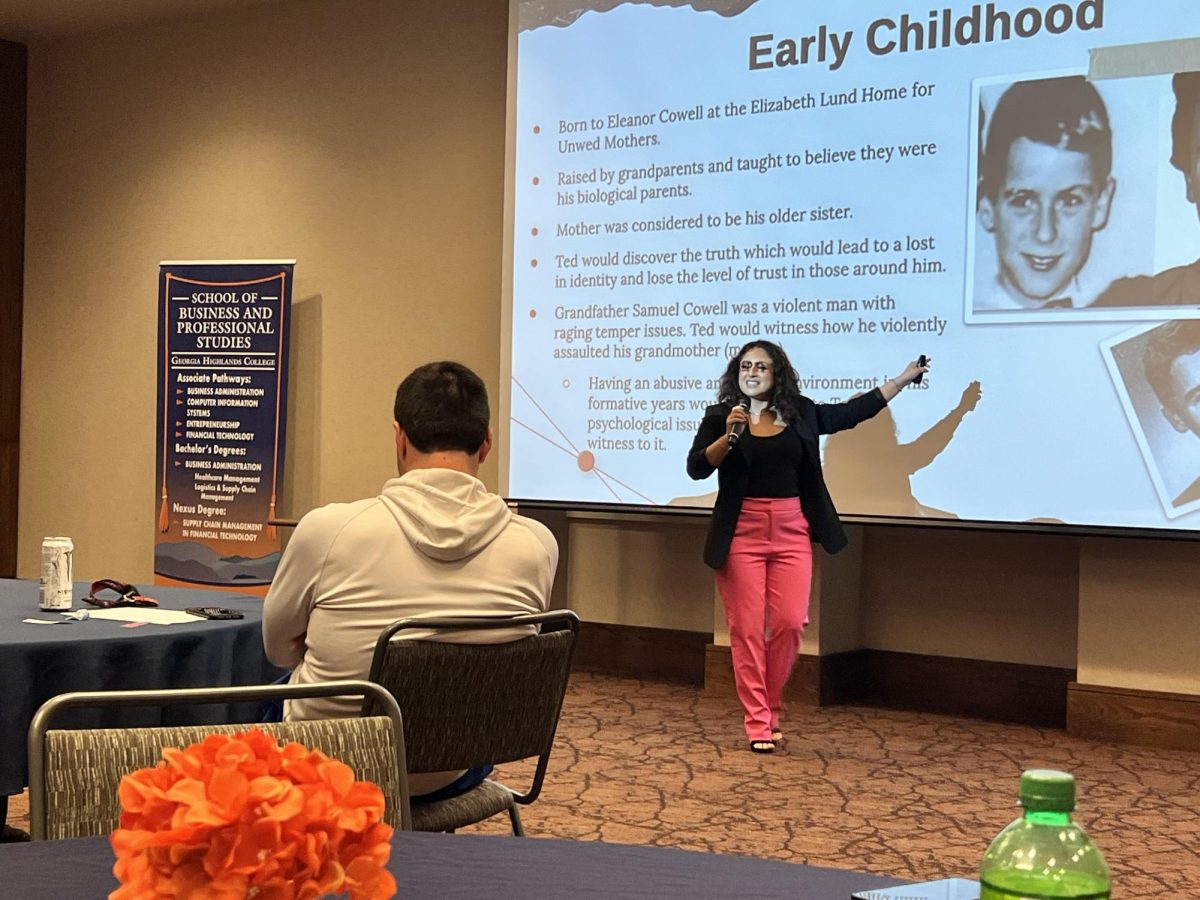

Photos by Russell Chesnut, Abby Chesnut.

The most striking difference visually between these cicadas is their color palettes — Georgia’s annual cicadas tend to be shades of green, while periodical cicadas are black with red eyes. Periodical cicadas are also smaller and have distinctly different songs than their annual cousins.

Northern counties in Georgia such as Gilmer, Union, and White are likely to see the insects popping up this summer.

“The densities [Brood X] can emerge in their highest concentration [and] can be as many as 1.5 million per acre!” said Christian, “North Georgia is at the lower part of their range that stretches across most of the eastern United States. Not everyone will see or hear the largest of the emergencies, as they are not distributed evenly over north Georgia. So some will encounter high densities and others may not even notice anything is happening.”

“The emergence is triggered when soil temperatures 8 inches down reach about 63-64 degrees, so in northwest Georgia that might be as early as late April or as late as mid-May,” said Christian.

Photo by Abby Chesnut

When the weather gets warm, thousands of cicadas will dig their way out of the ground and climb the nearest vertical surface to molt, leaving behind their exuviae, or molted exoskeletons. After the adult insects’ wings sclerotize or harden, they take off to find a mate.

Once they emerge, cicadas only live for a couple of weeks, but in that time they accomplish a lot. “The males use special organs in their abdomen to vibrate air in order to ‘sing’ their mating call,” said Christian.

“Most people are familiar with cicada singing,” said Christian, “even if they are not aware that is the sound you are hearing. To me it’s the sound of summer, when you are in nature during the day you hear various ‘hums’ coming from the area surrounding you, the most common thing making these noises are cicadas! Cicadas are known to be quite loud. Some species have been recorded producing over 100 decibels of noise in their mating calls — that’s about equivalent to a chain saw or motorcycle.

“When a female finds the singing to her liking, they will mate. She lays her eggs on a tree and then the adults die,” said Christian.

A few weeks later, their offspring hatch and make their way to the ground to start the 17-year cycle over again. Cicada nymphs spend most of their life burrowing underground and feeding on plant roots.

But why do they spend so long underground? Christian explained that cicadas do this to avoid predators. “Not all species spend that long underground,” said Christian, “But the staggering of years prevents too many species from syncing up with their predators. If everyone came out at the same time, then over enough time predators would respond similarly and it would be negative pressure on the survival of cicadas.”

“Cicadas are a big part of the food chain. It’s basically Thanksgiving dinner for almost every predator during these large emergencies,” said Christian. Birds, fish, rodents, and other insects are among the many predators of cicadas.

After 2021, Brood X will not be seen again until 2038. Georgia will see a few other broods before then, including the next emergence of Brood XIX in 2024 — which will be an even bigger event in Georgia than this summer. Even though cicadas don’t pose any danger to humans or pets, those with entomophobia may be tempted to stay indoors or travel out of state when 2024 rolls around!

Those of us who aren’t averse to creepy-crawlies can lend a hand to a scientific cause by helping to map Brood X’s emergence.

Anyone who sees or hears a cicada can record their sightings with the University of Connecticut’s Cicada Tracker or with the Cicada Safari app developed by Mount St. Joseph University. Scientists at the University of Connecticut are interested in tracking 2021 emergences in northern Georgia, in particular, as some of the cicadas here could be stragglers from Brood VI.

Abby Chesnut (She/They) majors in Business Administration and transferred to Kennesaw State University for marketing. A creative mind with a love of animals,...

Tom • Mar 15, 2021 at 8:51 pm

I, for one, graciously surrender my mind and body to the Swarm.

I strongly advise you to do the same, lest they assimilate you into their ranks more…gorily, than you may like.